Every community has different traditions surrounding the Mikvah, but I really loved this Syrian Mikvah ceremony because it included everyone.

On the morning of my son Sam’s wedding in Cancun, all the female guests woke up bright and early and dressed in white to accompany Estrella, his beautiful bride to the mikvah.

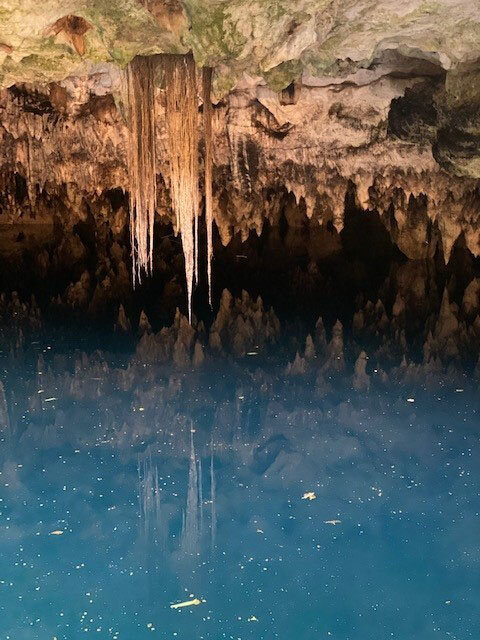

We drove away from our hotel to a secluded rainforest. This was not a typical mikvah, with fluorescent lighting, white tiles, railed steps to a heated pool and a Mikvah lady holding a terry cloth robe. Our bride was dipping in the Cenotes, the caves of Mexico’s Riviera Maya. Cenotes are natural pits that result from collapsed limestone bedrock that filters the rainwater to form blue swimming pools of crystal clear, fresh water.

Cenote Elvira, Quintana Roo Puerto Morelos

We enjoyed a delicious breakfast arranged by Estrella’s mother Denisse. The Rabbi’s wife explained the significance of the mikvah, the ritual purification ceremony.

Estrella’s mother, her grandmother Telly and her sister Ariella, the Rabbi’s wife and I, accompanied her down the steep, steep steps to the edge of the water.

We turned around to give her some privacy. She jumped into the water and submerged herself under the cool water. She came up and said the beracha, the blessing, then dunked another two times.

I closed my eyes and prayed that this would be the magical beginning of a long, healthy and fruitful marriage for my son and his beautiful bride.

When she emerged from the water, we hugged and kissed her and wished her well. The water was so tempting that Estrella’s friends came down to the water’s edge and pulled her back in for another swim.

Then we performed the traditional Syrian Mikvah ceremony, so thoughtfully organized by Estrella’s aunt Olga. We lit the bride’s candle and her close female relatives each lit a candle from her candle. We also read a prayer for the bride and groom wishing them much love, children, a happy home and long life. Mystically, we did not blow out the candles, but extinguished them. These candles were given to the bride for her to light the Shabbat candles in her home.

In a beautiful box, brought all the way from Mexico City, there is a huge Magen David ka’ak (crispy, salty cookie), surrounded by 52 smaller ka’ak cookies. Estrella’s mother and I take the large ka’ak and break it over the brides’s head. Estrella says the beracha “Bore mi’ne mezonot” and all the guests eat a piece of this traditional Syrian savory cookie. At this time, the bride blesses her friends and family with all their heart’s desires.

Rachel sheff and Denisse Levy breaking Ka’ak over bride Estrella Levy Sheff’s head.

The Sages say that a Magen David resembles a couple, with one side back and waist and on the other side, back and waist. Just as the Star is united, the newlywed couple should also be united for 120 years. Breaking the Star also reminds us of the destruction of the Beit Ha’Mikdash, the Holy Temple. The bride has the privilege of praying that it will be rebuilt soon. Symbolically, if there is an evil eye, the moment that we break the bread, the evil is also shattered.

The 52 smaller cookies represent the doubling of the numerical value of G-d’s name, Hashem, and that symbolizes that He should bring much beracha to the bride and groom.

Estrella’s talented grandmother made delicious marzipan confections and chocolate walnut balls and there were other cakes to ensure a marriage of sweetness, understanding and communication.

Every community has different traditions surrounding the Mikvah, but I really loved this Syrian Mikvah ceremony because it included everyone. When I married Neil, I went to the Mikvah alone with my mother and the rabbi’s wife. At our Henna party, some of the Rhodesli women made a Rosca, a sweet bread in the shape of a hand. They also broke it over my head. Estrella’s family comes from Mexico City, where there’s a large Syrian Jewish community and it’s wonderful that they have maintained these old traditions. It was filled with emotion and meaning, love and joy to have friends and family there. A perfect way to start the first day of the rest of your life.

Ka’ak Recipe

Ka’ak or Kahqa is the Arabic word for biscuit, but usually refers to a dry, hardened, crispy, salty, spiced ring-shaped cookie. The cookie appears simple to the naked eye, but the subtle flavor and flaky crunchiness makes them incredibly appealing and delicious. Ka’ak was described by the 11th century scholar and rabbi Hai Gaon as a hardened dry biscuit, with or without spices. Ka’ak are popular in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt and even Indonesia, among Jews, Christians and Moslems.

Based on Poopa Dweck’s recipe from Aromas of Aleppo.

3 tablespoons fresh yeast or 4 packages active dry yeast

2 tablespoons kosher salt

2 1/2 cups lukewarm water

8 cups all-purpose flour

1/3 cup anise seeds

1 teaspoon finely crushed mahlab (sour cherry pit can purchase on Amazon), optional

1 teaspoon ground coriander

1 teaspoon ground cumin

2 teaspoons nigella seeds

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1 teaspoon sugar

1 cup Earth Balance

1 egg

¼ cup sesame seeds

In a mixing bowl, sprinkle yeast and salt over 2½ cups lukewarm water. Let the mixture stand for about 5 to 10 minutes, until bubbles appear on the surface of the mixture.

Put flour in a large mixing bowl and form a well in the center.

Add the anise seed, mahlab, coriander seed, cumin, vegetable oil, sugar and vegetable shortening and stir until well combined.

Then slowly incorporate the yeast mixture into the well, absorbing flour and mix thoroughly, by hand.

Knead the dough for about 10 minutes until it is soft and smooth. Dough should not stick to the sides of the bowl. If the dough is sticky, gradually add one tablespoon of flour until texture is smooth.

Cover the dough with plastic wrap and a towel. Let the dough rise for 1½ hours in a warm place in your kitchen.

Preheat oven to 400°F.

On a lightly floured work surface, punch down the dough and divide it in 4.

Roll a piece of the dough into a 2-inch-diameter log.

Cut the log into ½-inch rounds and roll each of the rounds to a length of about 4 inch rope. You can crimp the edges of the ka’ak to give them a pretty and traditional appearance, with a sharp knife, make 1/8-inch notches along one long edge of each dough strip.

Shape each strip into a ring, crimped edges facing outward. Brush each ring of dough lightly with the egg wash. Then dip each dough ring in sesame seeds.

Place the ka’ak on a parchment-lined baking tray in rows.

Bake for 10 minutes, use all the racks in your oven and rotate the trays during the baking.

When all the ka’ak are completely baked, reduce the oven temperature to 250°F and bake for an additional 20 minutes.

Then crisp the ka’ak by reducing oven temperature to 200°F for 20 minutes. This stage is essential to produce the crunch and texture desired.

The ka’ak should appear golden and crisp.

Let cool and store in an airtight container.